A Historian’s Perspective

The Valley Floor—A National Perspective

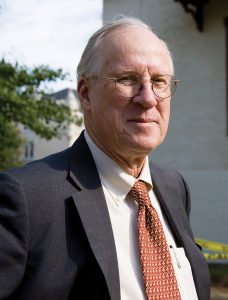

By Richard Moe

Richard Moe was president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the nation’s largest preservation organization, based in Washington D.C., from 1993 to 2010. He is also a part-time Ophir resident. This commentary was written in August 2001 and the Valley Floor was placed on the National Trust’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list later that year.

By Richard Moe

The American people are learning to love their historic places as never before. The problem is that in some cases they are loving them to death.

People are especially flocking in record numbers to upscale historic resort communities like Martha’s Vineyard, Santa Fe and, of course, Telluride, primarily because these places uniquely combine natural beauty with a preserved historic community. But, increasingly, they are coming under enormous pressures that threaten the characteristics that make them so special.

The consequences are all too familiar. People who work in many of these places can no longer afford to live there. Once distinctive downtowns are transformed into thinly disguised strip malls. And, alarmingly, attractive older homes are demolished and replaced with “McMansions” that are totally inappropriate in scale and design to their surroundings.

This past June, the National Trust for Historic Preservation put Nantucket Island on its 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list to bring attention to this growing “tear-down” phenomenon.

Thanks to a broad and deep commitment to preserving its historic character, Telluride has probably dealt with these pressures more effectively than any other historic community in the country, certainly better than places like Aspen or Park City. New in-fill construction, for the most part, has blended in with existing streetscapes. Restorations have been largely faithful to original designs and materials. And, importantly, the bulk of new development has been far enough removed from the town itself so as not to collide with or compromise its contextual integrity.

All of these things combine to make Telluride a place that appreciates its heritage and uses it in enlightened ways to provide an enviable quality of life for its residents and visitors.

Allow the Valley Floor to be developed, however, and that will inevitably change, perhaps not all at once but certainly over time. It will place Telluride on a slippery slope to becoming just another resort that puts a higher premium on commercial development than on preserving its natural and cultural heritage. It will send an unmistakable signal that this is not such a special place after all, and that will almost certainly mean fewer people coming here either to visit or to live. Travel writer Arthur Frommer says that people do not come to places that have “lost their soul.”

The economic case against developing the floor deserves more attention than it has received, particularly from those whose livelihoods depend on increased visitation. But as strong as it is, it is not the most compelling case. That belongs to the undeniable fact that Telluride’s physical character and integrity will be profoundly and forever compromised by the loss of its context.

The two things that provide Telluride’s context are the mountains that surround it and the Valley Floor that is its approach—its front yard. Take either of them away and you have a different place, a much lesser place. A national historic landmark district like Telluride does not exist in a vacuum; it exists in a context and it depends on that context for integrity.

In the end, issues such as this invariably come down to a question of values, and it is encouraging to see so many in the area coming down on the side of valuing the Valley Floor’s beauty and heritage. But there are obviously powerful forces on the other side who don’t share those values and whose considerable resources may, in the end, allow them to prevail.

Maybe Telluride should be a candidate for the National Trust’s 2001 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list.